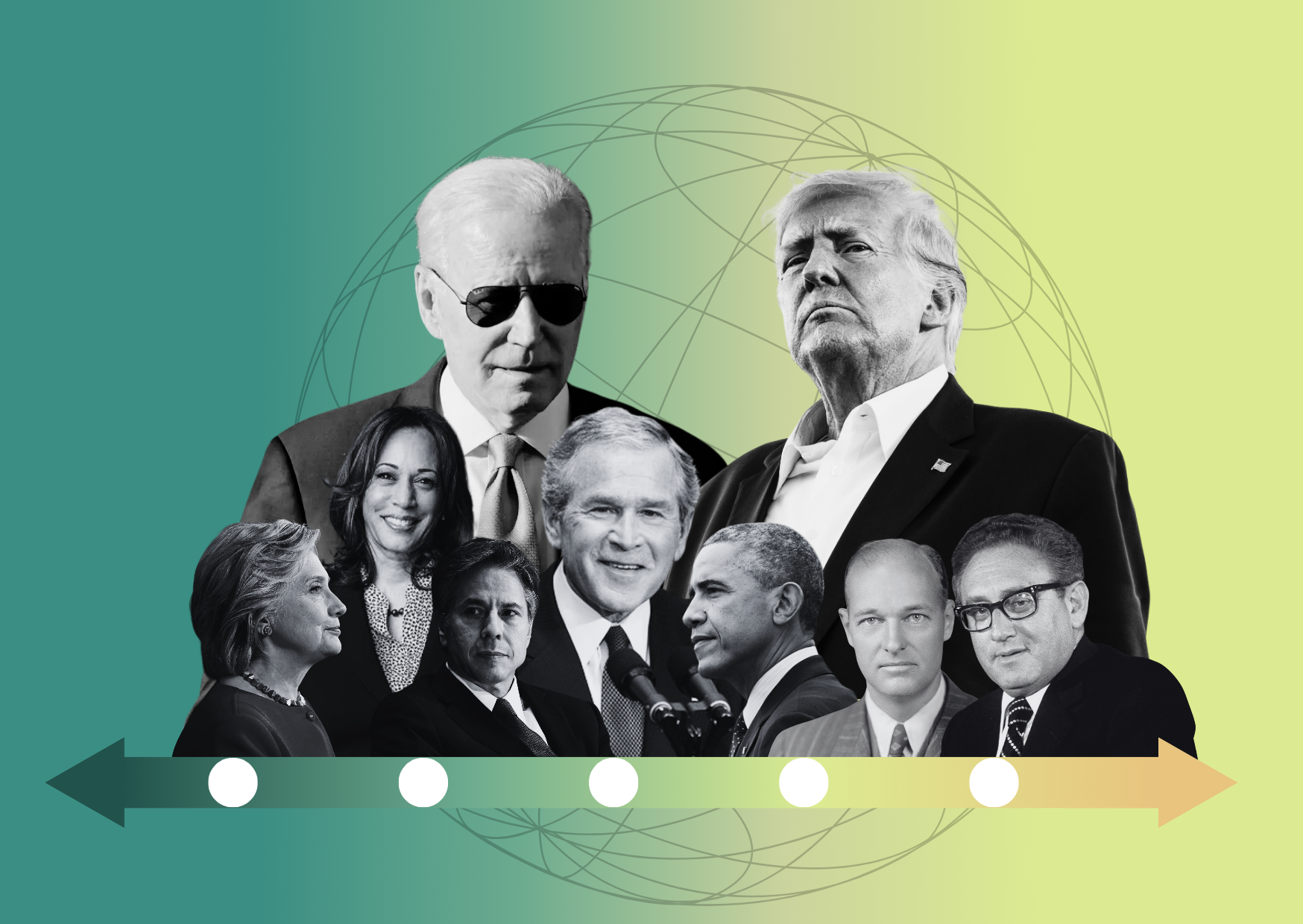

School Of Thought That Influenced American Foreign Policy

H.W. Brands’ article delves into Walter Russell Mead’s “Four Schoolmasters” framework, where Hamiltonian, Jeffersonian, Jacksonian, and Wilsonian ideals shape U.S. foreign policy.

By | Kerem Karacay,

5 MAY, 2024 | 11:29 PM

H.W. Brands’ article on the “Four Schoolmasters” of American foreign policy, based on Walter Russell Mead’s book “Special Providence,” articulates a unique perspective on the underpinnings of the United States’ approach to international relations. In his article, Brands divides the patterns and approaches to foreign policy of the U.S. Presidents into four categories, naming them after the U.S. statesmen who pioneered these approaches. When taken a closer look, their influences in one way or another can be traced in the foreign policy approach of every U.S. President and their administration.

These “schools of foreign policy,” as we would call them, serve as a unique tool for navigating the characteristic patterns of the foreign policy approaches the U.S. Presidents adopted throughout their terms in office.

The four “schoolmasters” or schools of thought Mead identifies are:

1. Hamiltonian: This school, named after Alexander Hamilton, views the world primarily as a marketplace. It advocates for enhancing America’s position in global commerce, emphasising the growth of commerce and the institutions supporting it as essential to foreign policy. Hamiltonians have historically supported cooperation with leading trade nations and are seen as conservatives who doubt human perfectibility but are optimistic about the benefits of commerce.

The first example of Hamiltonianism in U.S. Foreign policy would be George Washington. As the first president, Washington’s policies were heavily influenced by Alexander Hamilton, who focused on economic stability and established the United States as a credible participant in international trade. Ronald Reagan is also often considered a Hamiltonian due to his emphasis on economic strength and global trade as fundamental aspects of U.S. foreign policy. We can see how his approach lies at the core of the Reagan administration’s stance on the Cold War. It can even be considered in this era that the United States pursued a war of economic attrition with the Soviet Union, aiming to collapse it not by the use of hard power instruments but by aiming to paralyse the Soviet Union’s means of production by forcing them to focus on the arms race and defence spendings.

2. Jeffersonian: Emerging in opposition to Hamiltonian principles, the Jeffersonian school prioritises democracy, believing it arises not as a side effect of commerce but through deliberate effort. Jeffersonians value individualism and are wary of institutions, especially commercial ones, potentially corrupting personal virtue. They have been labelled as isolationists or nationalists due to their preference for focusing on the domestic perfection of democracy over engaging in international affairs. Thomas Jefferson is the archetype for this school of thought. He was intensely focused on democracy and cautious about foreign entanglements, prioritising domestic democratic development. Jimmy Carter is another example of a Jeffersonian school. His emphasis on human rights and cautious approach to military intervention align directly with Jeffersonian ideals.

3. Jacksonian: Although Jacksonians share a domestic focus, they have been behind some of the most assertive American foreign policies in history. They are populists who believe in democracy emerging from the people and display a belligerent nationalism, quick to defend American honour and interests. Jacksonians support strong defence spending and are focused on American victory rather than global salvation. Andrew Jackson is the namesake of this school. Jackson’s policies were nationalist and populist, emphasising strong military posture and territorial expansion. Though not a perfect match, Theodore Roosevelt also had some influences of Jacksonianism on his approach. Roosevelt’s assertive foreign policy, including the “Big Stick” ideology, aligns with the Jacksonian emphasis on national honour and military strength. Former U.S. President Donald Trump also heavily reflects Jacksonian characteristics in his foreign policy approach. This will be referred to later in this article.

4. Wilsonian: Named after President Woodrow Wilson, Wilsonians believe in America’s mission to save the world and make it “safe for democracy.” They have often allied with Jeffersonians over the value of democracy but differ in that they see engagement with the world as essential to preserving democracy at home. Contrary to Jacksonians, Wilsonians are liberal internationalists who support international institutions and cooperative global efforts. Woodrow Wilson, the foundational figure for Wilsonianism, promoted internationalism and the idea that the U.S. has a moral obligation to spread democracy and peace worldwide. Wilsonian Principles and the formation of the League of Nations after World War I were efforts to build a set of morals and order for the world “under the light of American Democracy.” Franklin D. Roosevelt’s leadership during World War II and his efforts to establish the United Nations echoed Wilsonian ideals. It can even be seen as a “second go” for Wilsonian aims, this time with a stronger foundation.

When we take a look at the recent U.S. presidents and how they fit into these schools first thing that comes across is them having reflections from multiple schools of thought in their foreing policy approach. They don’t fit into only one of those schools for each. George W. Bush would be considered mostly Jacksonian. Regrettably, especially post-9/11 we see his foreign policy approach is shape-shifting with elements of Wilsonian interventionism as well (e.g., Iraq War). Barack Obama, on the other hand, is primarily Wilsonian with his emphasis on multilateralism and diplomacy, but also has Jeffersonian tendencies in his cautious foreign policy approach.

Donald Trump carries predominantly Jacksonian characteristics with his “America First” policy. His scepticism towards international agreements (e.g., the Paris Climate Deal and the TPP) and institutions such as the United Nations, NATO, and the European Union, as well as his populist rhetoric in general, The current U.S. president at the time this article was being written Joe Biden, is a blend of Wilsonian and Hamiltonian schools. Focusing on restoring alliances, engaging with international institutions, and promoting global economic stability are the main pillars of Biden’s foreign policy approach. Mead’s taxonomy categorises Hamiltonians and Wilsonians as conservative and liberal internationalists, respectively, while Jacksonians and Jeffersonians are seen as conservative and liberal nationalists.

The distinctions are theoretical and reflect historical inconsistencies and the complex nature of American foreign policy. Mead aims to offer a historical perspective that also serves as a guide for future policy directions, suggesting that understanding these schools of thought is critical to navigating the challenges of the 21st century. These categories are not rigid, and many presidents exhibit traits from multiple schools at different times. Mead’s model is a lens through which one can interpret U.S. foreign policy’s complexities and shifting priorities throughout its history. It must be remembered, though, that especially as we look at U.S. Foreign Policy and Presidents affiliated with it in the 21st century, it gets harder to put these administrations under singular categories. Since the end of the Cold War and 9/11, the dynamics of international relations have changed and cary on to change.